Visit the Early Man 2 online viewing room here

Adam Parker Smith, Amalia Angulo Alvarez, Barry McGee, David Shrigley, Ellon Gibbs, Eric Louie, Hunter Amos, JIM JOE, Joe Bradley, Katherine Bernhardt, Luke Murphy, Misaki Kawai, Ohad Meromi, Théo Viardin, Ugo Rondinone, Lee Dawson, and Xavier Baxter.

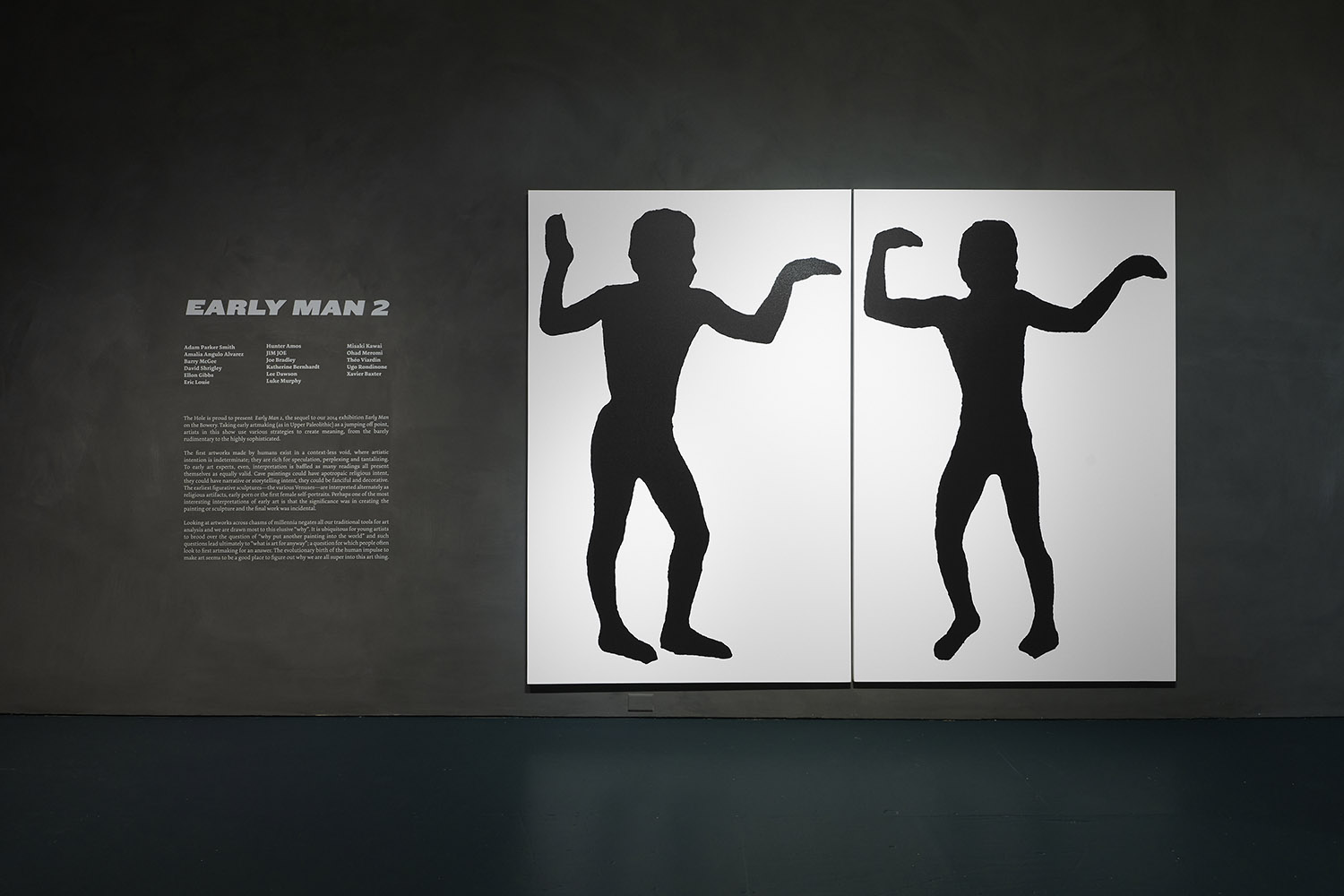

The Hole is proud to present Early Man 2, the sequel to our 2014 exhibition Early Man on the Bowery. Taking early art making (as in Upper Paleolithic) as a jumping off point, artists in this show use various strategies to create meaning, from the barely rudimentary to the highly sophisticated. Ten years on, this version includes several of the original Early Man artists: Katherine Bernhardt, Misaki Kawai, Barry McGee or David Shrigley alongside many new names like Ellon Gibbs to Amalia Angulo Alvarez or Théo Viardin.

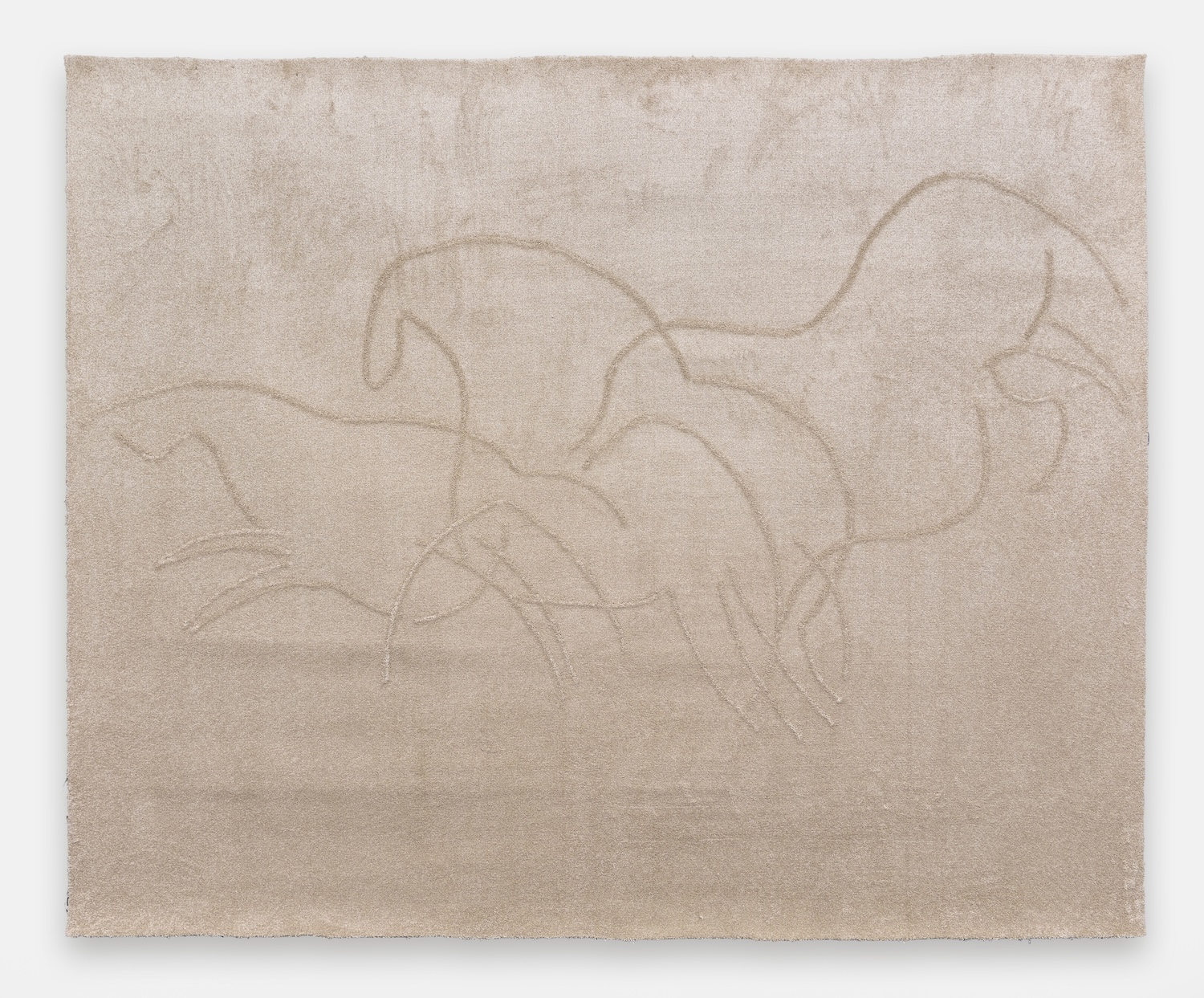

Adam Parker Smith’s newest carpet painting Paleolithic Horses begins at the beginning, drawing mankind’s first artworks with his finger in shag carpet. This mode of making reflects our human resourcefulness pre-Blick to get our feelings out there fast, while Barry McGee captures the most primal human urge of scribbling on surfaces—something graffiti writers are intimately familiar with— asserting our existence upon the world around us.

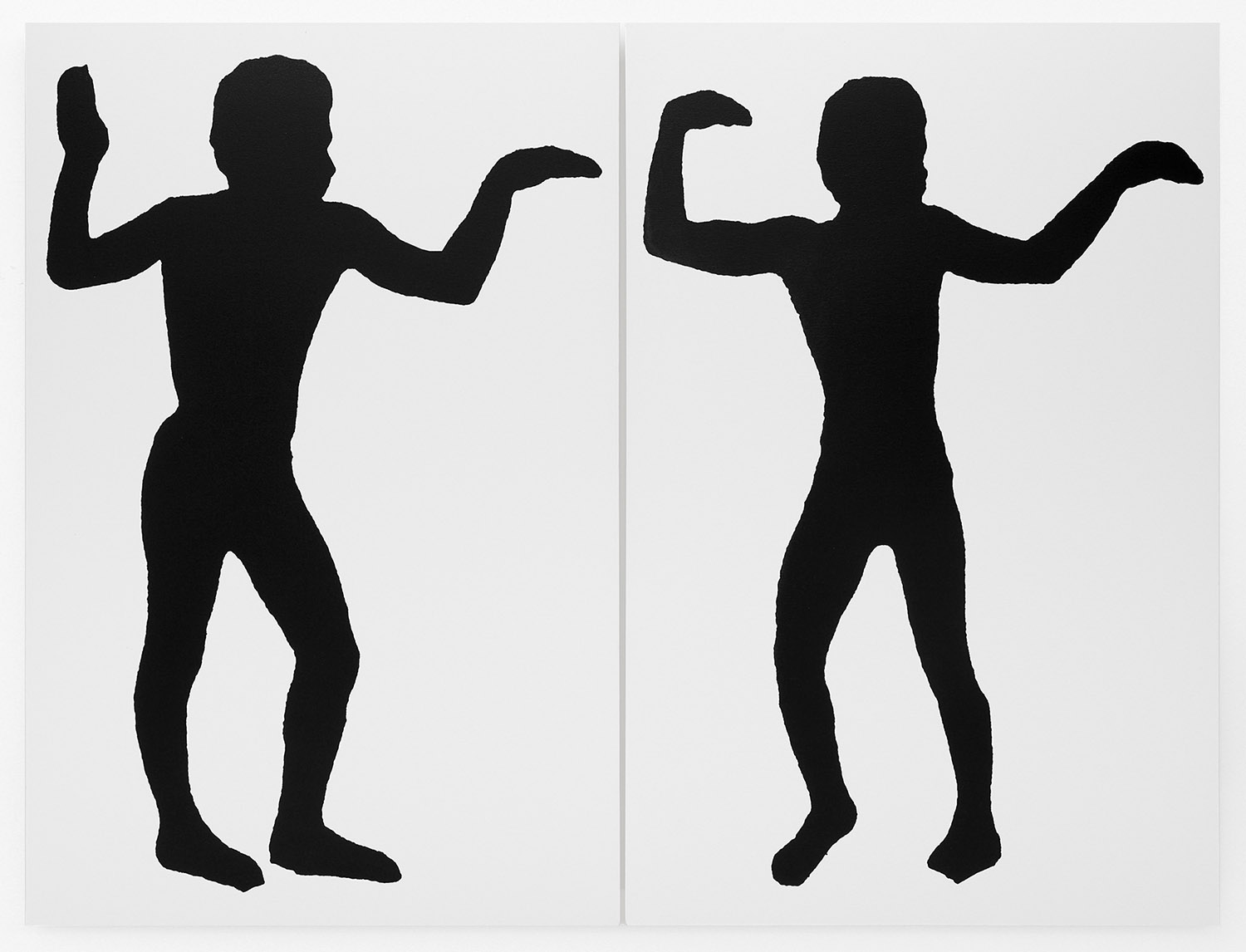

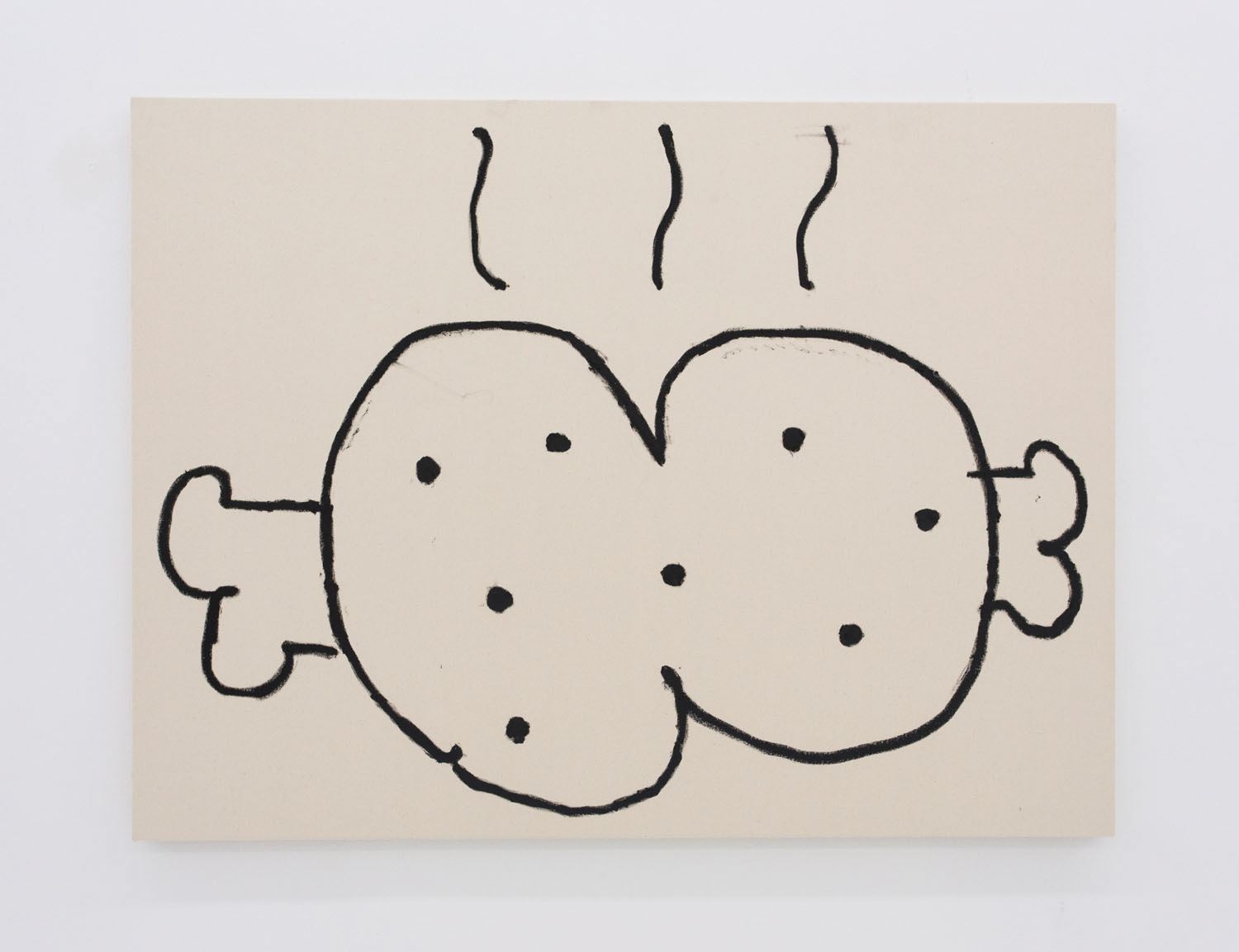

Caveman style, Misaki Kawai’s Steamy Dinner and Meaty Bone benches and Joe Bradley’s Untitled (Human Form) silhouettes provide strange new glyphs for our puzzlement. Are we dancing? Are we signaling danger? Ohad Meromi illustrates the former in larger-than-life sculpture The Spirit of the Dance allowing us to ponder whether the first art making was perhaps choreography.

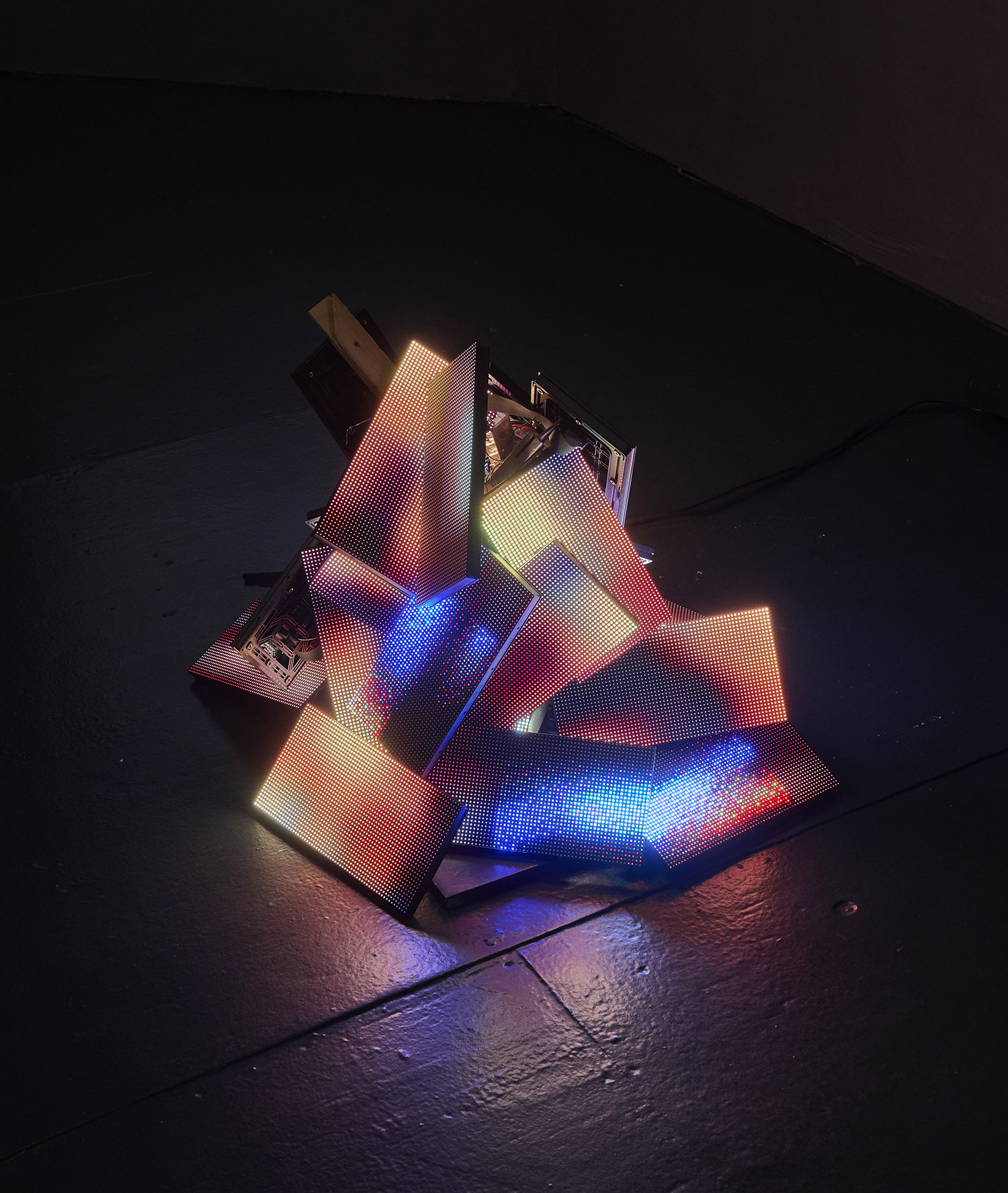

In the very rear of the space, Luke Murphy’s FirePile sculpture illuminates our dark neanderthal night using LED Matrix Panels and video hardware. Eric Louie’s oil and acrylic paintings surround us in a sparkle cave of minerals while some bold and gestural human forms are painted at pace by Xavier Baxter and Hunter Amos.

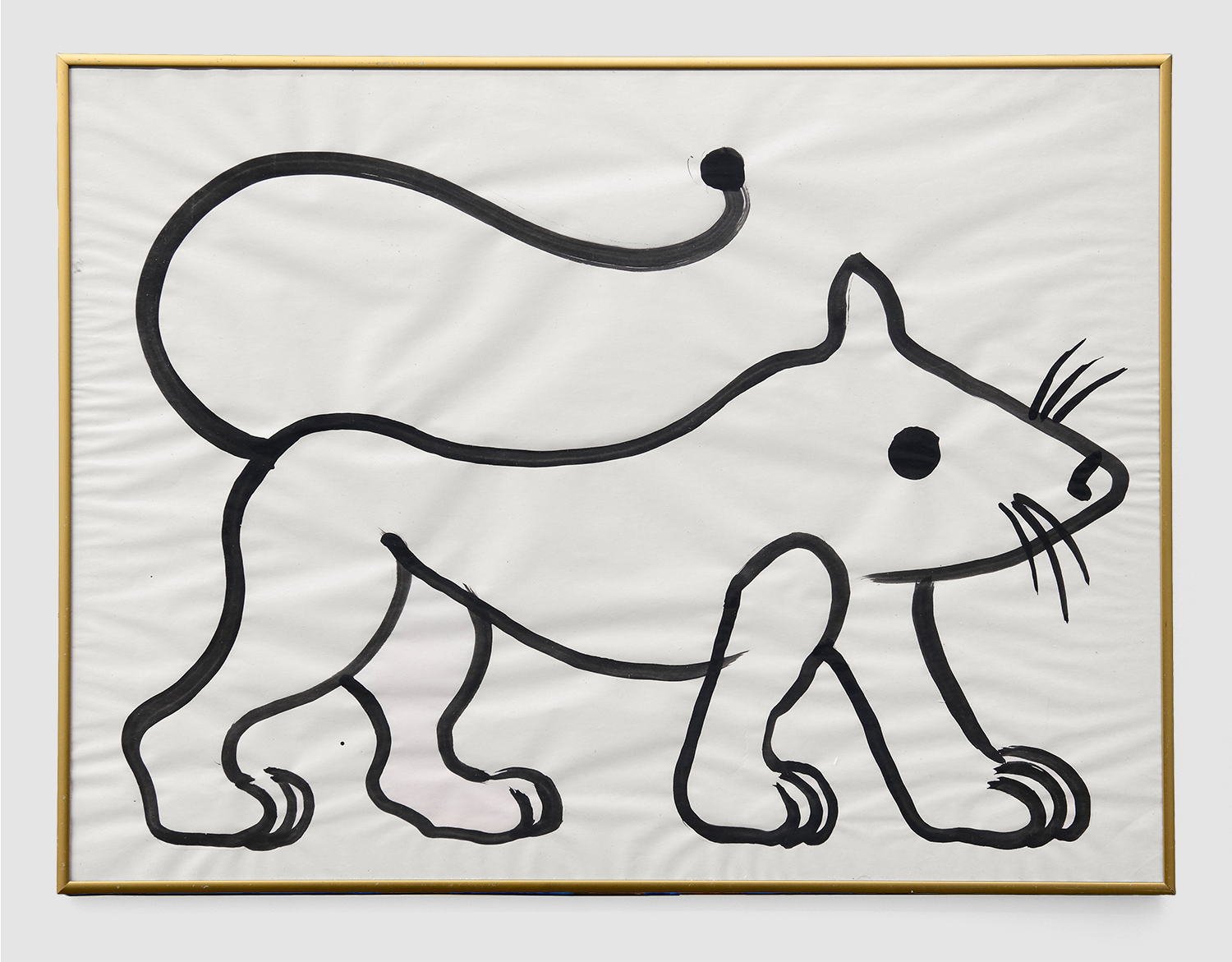

Katherine Bernhardt, Magically Delicious, gives us a confused alien surrounded by cereal, just as obtuse as her 2014 pizza and coffee maker painting: symbology detached from meaning like the marshmallowy Lucky Charms. JIM JOE makes a uniquely New York glyph for us: a hybrid of the NYPL lion and a rat. And Ugo Rondinone shows us just a rock, but one that we literally cannot help ourselves projecting a face and human qualities onto.

Ellon Gibbs is a sincere standout amongst the detached: two figures marvel at the sky and the unspoiled natural world around them, evoking the kind of wonderment one might imagine early man experienced when everything was still to be discovered.

We are assembling this team because they have a shared vibe but diverse output: I used to do more shows like this—that questioned artmaking itself—and thus I used to write much longer press releases:

The first artworks made by humans exist in a context-less void, where artistic intention is indeterminate; they are rich for speculation, perplexing and tantalizing. To early art experts, even, interpretation is baffled as many readings all present themselves as equally valid. Cave paintings could have apotropaic religious intent, they could have narrative or storytelling intent, they could be fanciful and decorative. The earliest figurative sculptures—the various Venuses—are interpreted alternately as religious artifacts, early porn, or the first female self-portraits. Perhaps one of the most interesting interpretations of early art is that the significance was in creating the painting or sculpture and the final work was incidental.

Looking at artworks across chasms of millennia negates all our traditional tools for art analysis and we are drawn most to this elusive “why”. It is ubiquitous for young artists to brood over the question of “why put another painting into the world” and such questions lead ultimately to “what is art for anyway”; a question for which people often look to first art making for an answer. The evolutionary birth of the human impulse to make art seems to be a good place to figure out why we are all super into this art thing.

The accepted story is that art went from being functional craft to being capital-A Art around the Renaissance, so it would be impossible for us to look at prehistoric art properly from our historical vantage point. Symbolic practicality seems to be our cultural knee-jerk; but is “art for art’s sake” so impossible to imagine for Early Man? The patterns of petroglyphs and pictograms seem to prove the pleasure of iteration early on. The accomplishment of verisimilitude in 30,000-year-old animal paintings in Chauvet or Lascaux seems to evince the simple enjoyment of rendering accurately.

Other than real-world early art impulses, the stock character of the Cave Man holds a lot of appeal for young artists; the idea that art was urgent, crucial, important enough to make time for during a strenuous day of hunting or running from mammoths or whatever. Maybe artists are interested in the idea of a cultivated ignorance or the appearance of uncivilized behavior; maybe artists also like the fantasy that their work will be something generations will puzzle over in the future, or are just into the idea of being willfully confusing, their intentions unexplained, the way a 23,000 year old Baton de Commandement could be a spear thrower or a midwife calendar or a dress fastener or an arrow straightener.

I think I was originally drawn to making a thematic show around these ideas after seeing a lot of aggressive, raw and rugged painting over the past year, made even with the artist’s hands, really getting in there and seeking what you could call gymnastic authenticity. I saw these paintings as like literally wrestling meaningfulness and cramming it into an artwork.

But since then and as this show came together I have been more drawn to the pre-symbolic and the obtuse, creating a work that can hover outside of time and interpretation, that deflects the exhausted and exhausting pathways of looking at art that bore the shit out of me sometimes. Drawing on the tradition of Modernity and all its offshoots sometimes feels tail-chasey; Primitivism is patronizing; what about just getting down with artworks made by the first humans?

Joe Bradley, Untitled (Human Form), 2010, silkscreen on canvas, diptych, 96 x 63 inches, 244 x 160 cm.

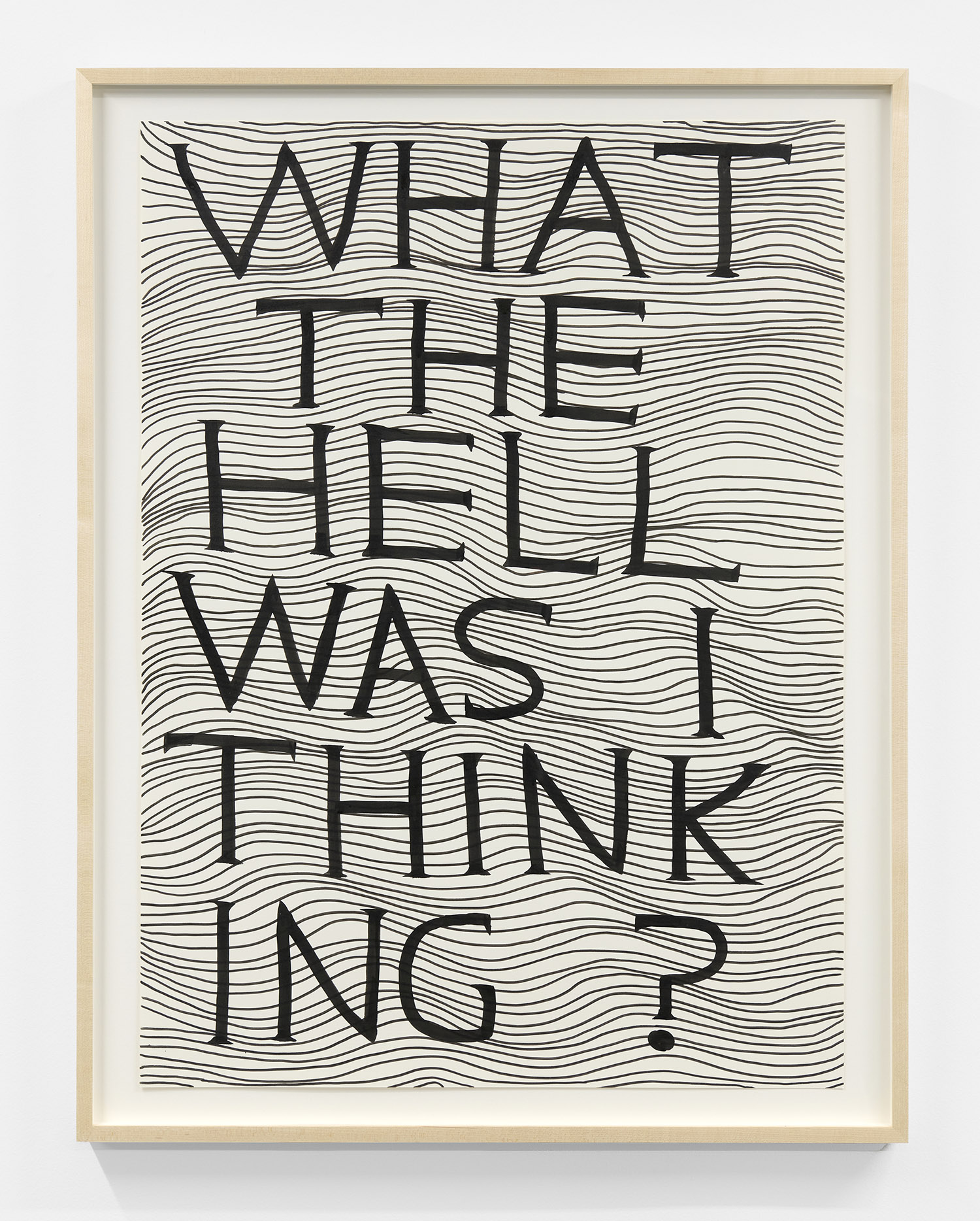

David Shrigley, Untitled (What The Hell Was I Thinking), 2023, acrylic on paper, 30 x 22.5 inches, 76 x 56 cm, framed: 33 x 25 inches, 84 x 64 cm.

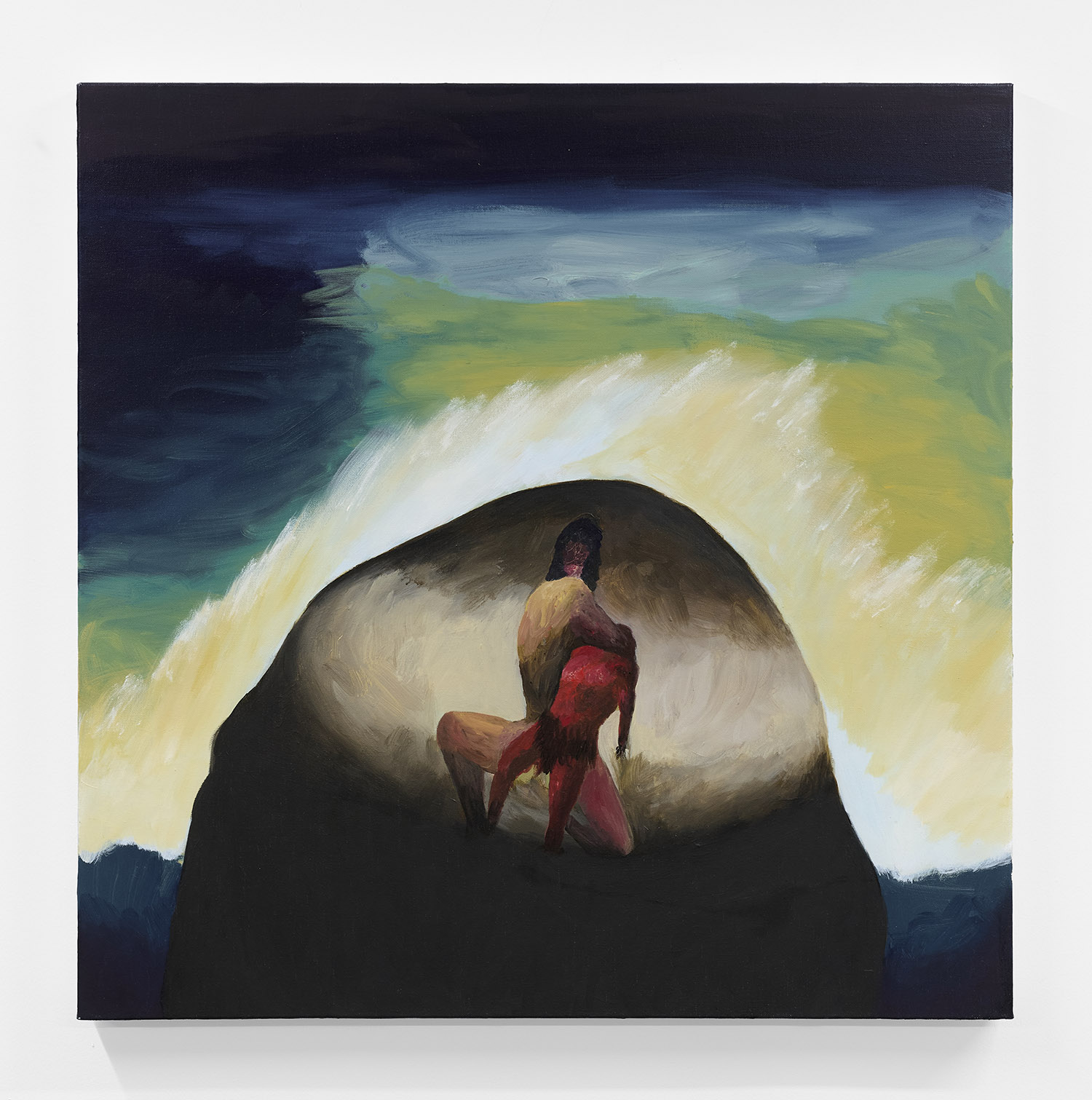

Théo Viardin, Study For A Wound I, 2024, oil on linen, 57 x 45 inches, 146 x 114 cm.

Ellon Gibbs, Wholy Holy, 2024, oil and acrylic on canvas, 52 x 76 inches, 132 x 193 cm.

Ellon Gibbs, Life’s Hardship, 2023, acrylic on panel, 30 x 30 inches, 76 x 76 cm.

Katherine Bernhardt, Magicaly Delicious, 2023, acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 72 x 78 inches, 183 x 198 cm.

Luke Murphy, Fire Pile 3.0, 2024, LED matrix panels, wood stretcher bars, wire, video hardware, sofware, code, 28 x 25 x 24 inches, 71 x 63.5 x 61 cm.

Ohad Meromi, The Spirit Of The Dance, 2022, polyurethane foam, 120 x 80 x 42 inches, 305 x 203 x 107 cm.

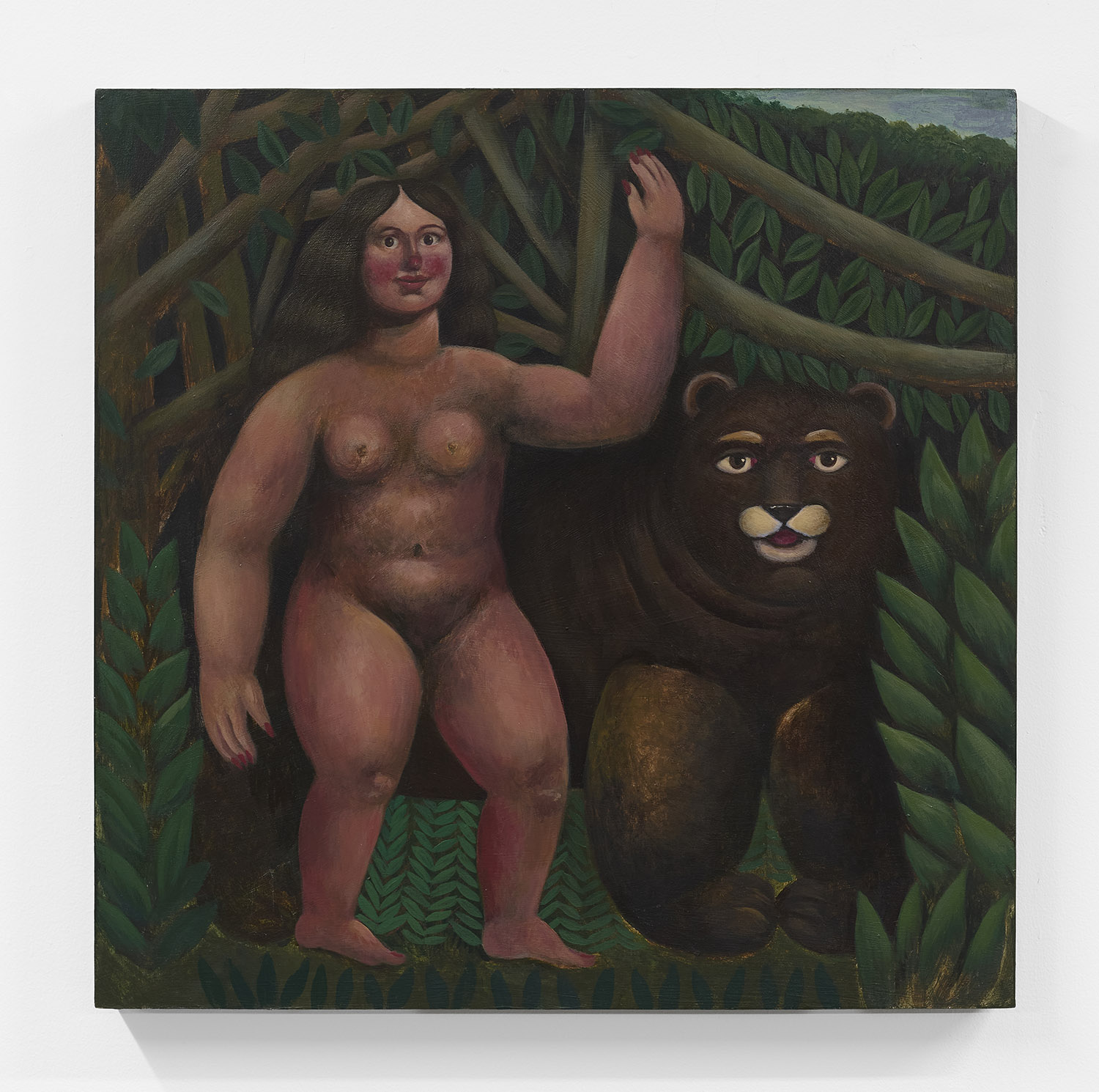

Amalia Angulo Alvarez, Woman with Bear, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 20 x 20 inches, 51 x 51 cm.

Xavier Baxter, In the Dark, 2024, oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches, 152 x 183 cm.

Hunter Amos, Kinail, 2024, acrylic, oil, plaster, salvaged metal, 62 x 51 inches, 157 x 130 cm.

Eric Louie, Green Eyes, 2024, oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches, 122 x 122 cm.

Eric Louie, Reunion, 2024, oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches, 122 x 122 cm.

Eric Louie, Just Like Paradise, 2024, oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches, 122 x 122 cm.

Misaki Kawai, Steamy Dinner, 2016, oil stick on canvas, 36 x 48 inches, 121.9 x 91.4 cm.

Misaki Kawai, Meaty Bone Bench, 2016, acrylic on masonite, 21 x 13 3/4 x 68 3/4 inches, 34.9 x 53.3 x 174.6 cm.

Jim Joe, RAT LION (PROTO HISTORY), 2024, gouache on newsprint in found frame, 18 x 24 inches, 46 x 58 cm, framed: 18.5 x 24.5 x 1 inches, 47 x 61 x 2.5 cm.

Ugo Rondinone, the loud + the quiet, 2023, stone, 11 x 9 1/8 x 4 3/4 inches, 28 x 23 x 12 cm.

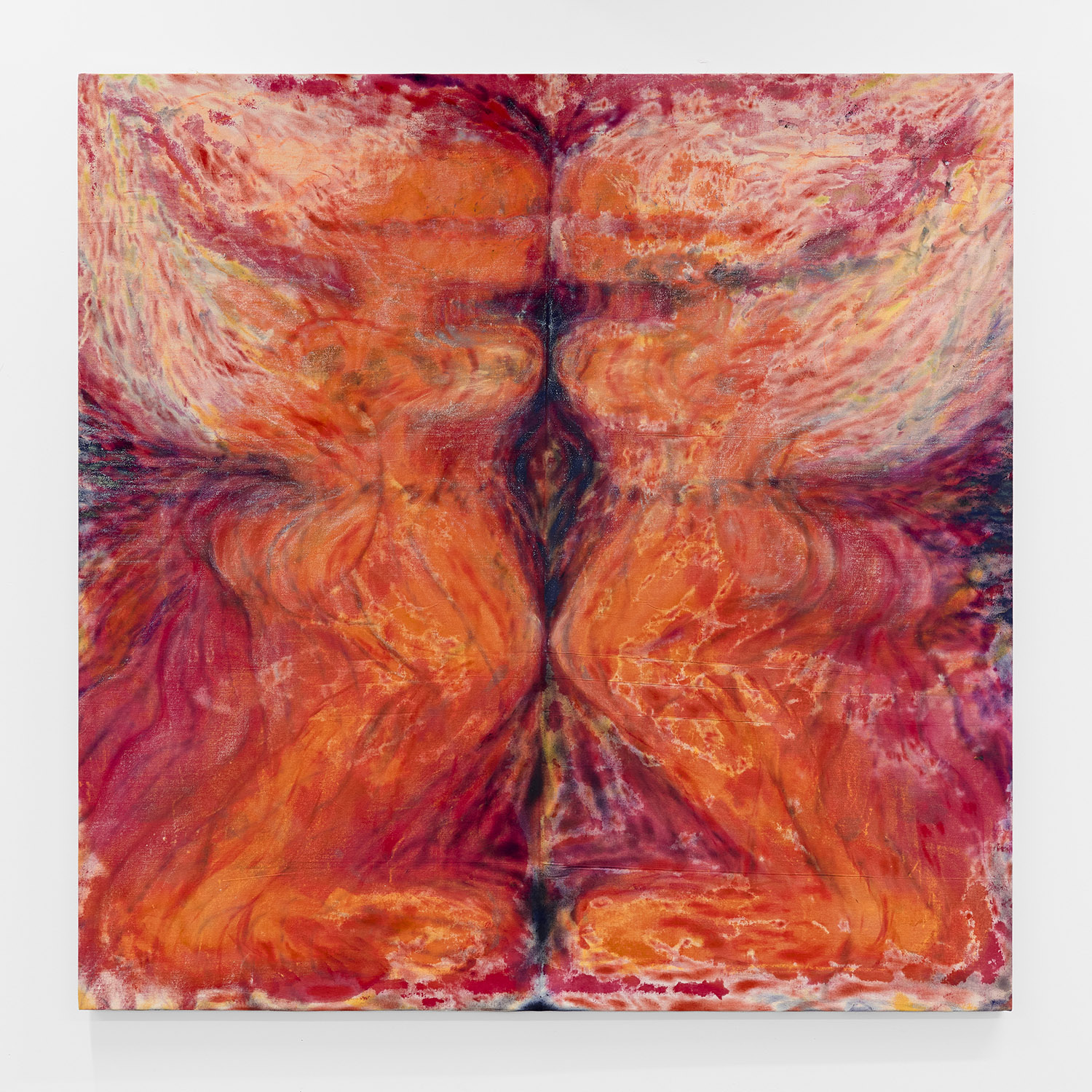

Lee Dawson, Of Being, 2024, oil paint and dye on canvas, 57 x 57 inches, 145 x 145 cm.

Barry McGee, Untitled, 2024, mixed media and gouache on found paper, 15 x 21 x 0.5 inches, 38 x 53 x 1.3 cm.

Adam Parker Smith, Paleolithic Horses, carpet, 108 x 144 inches, 274 x 366 cm.