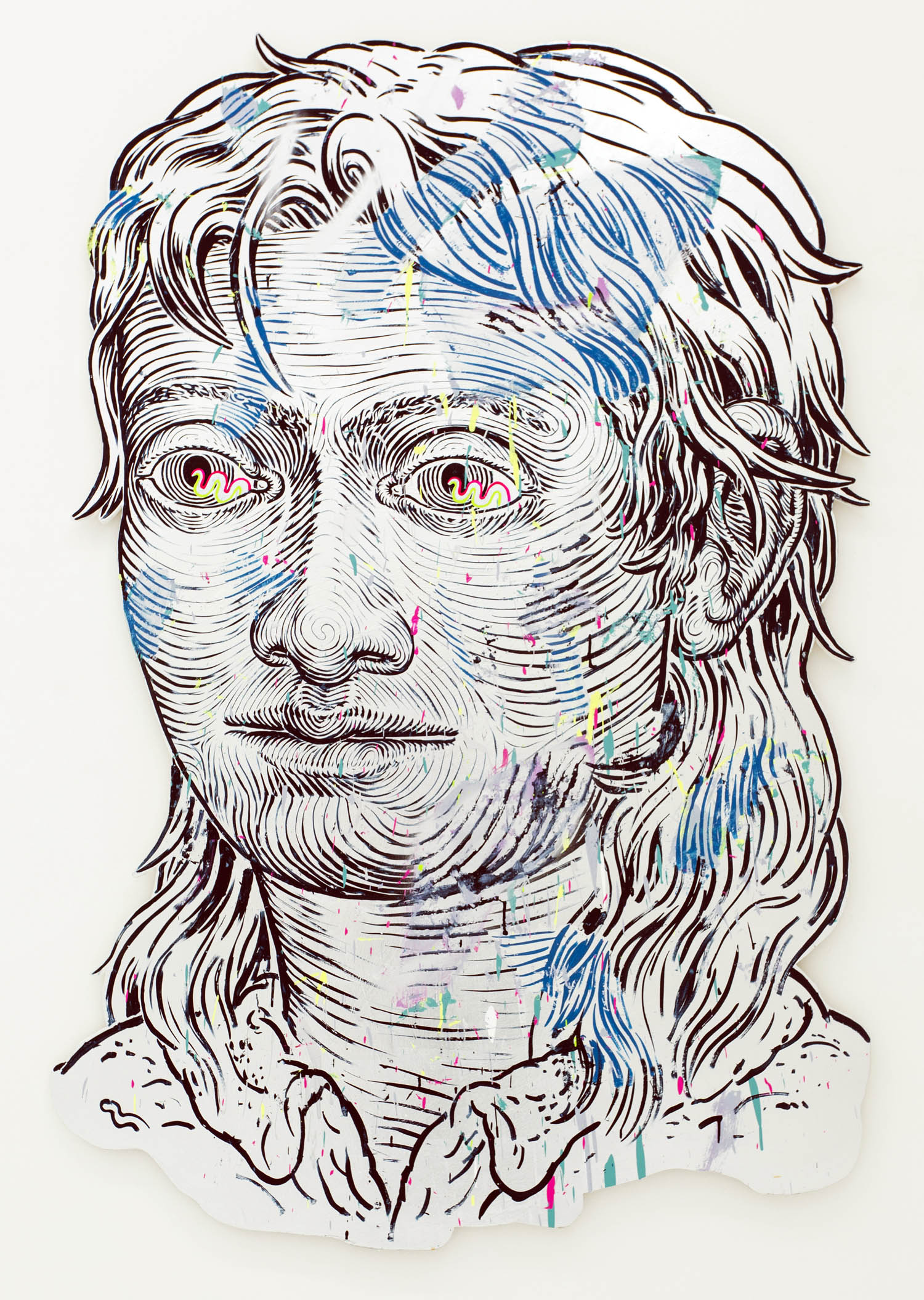

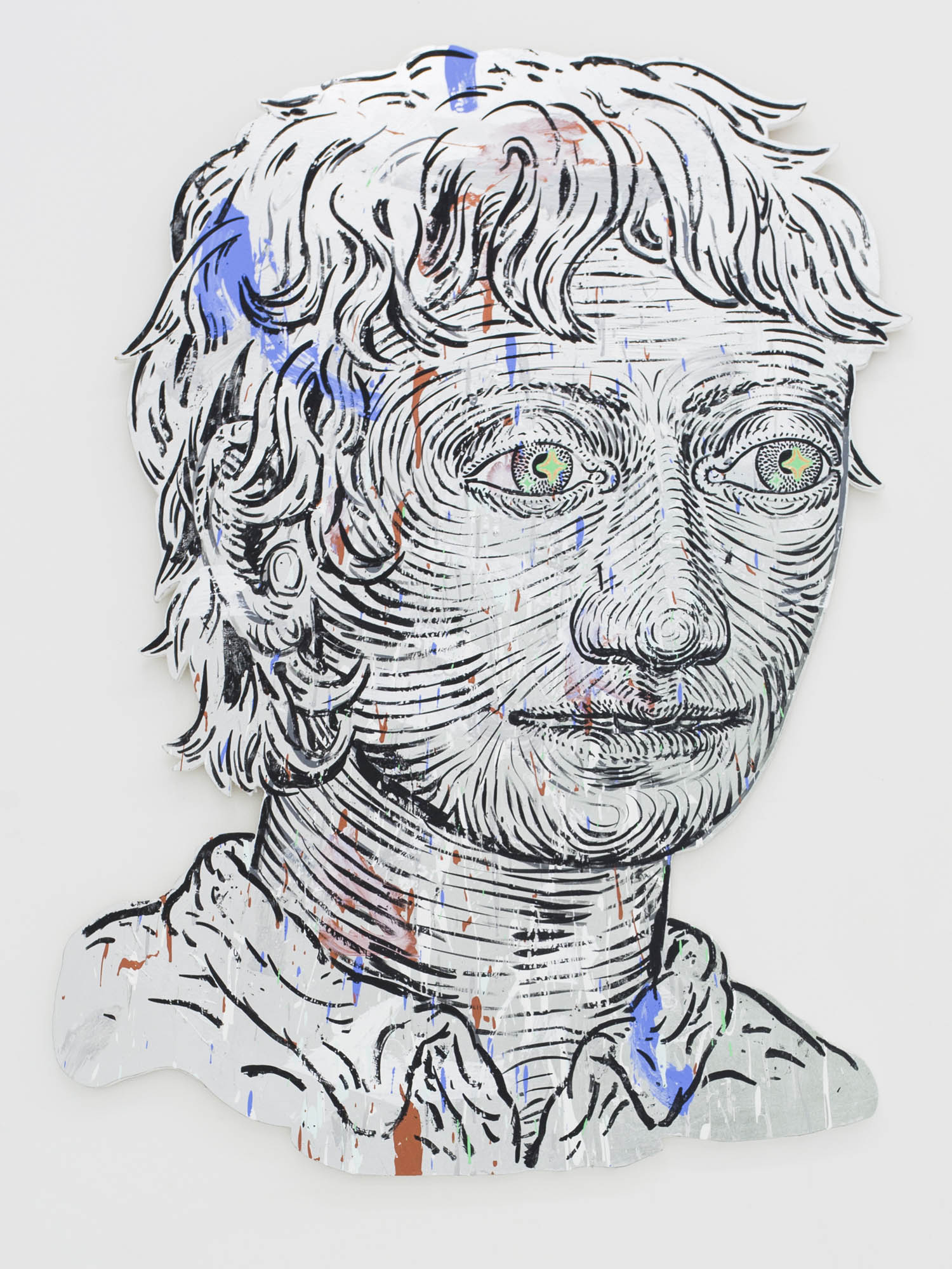

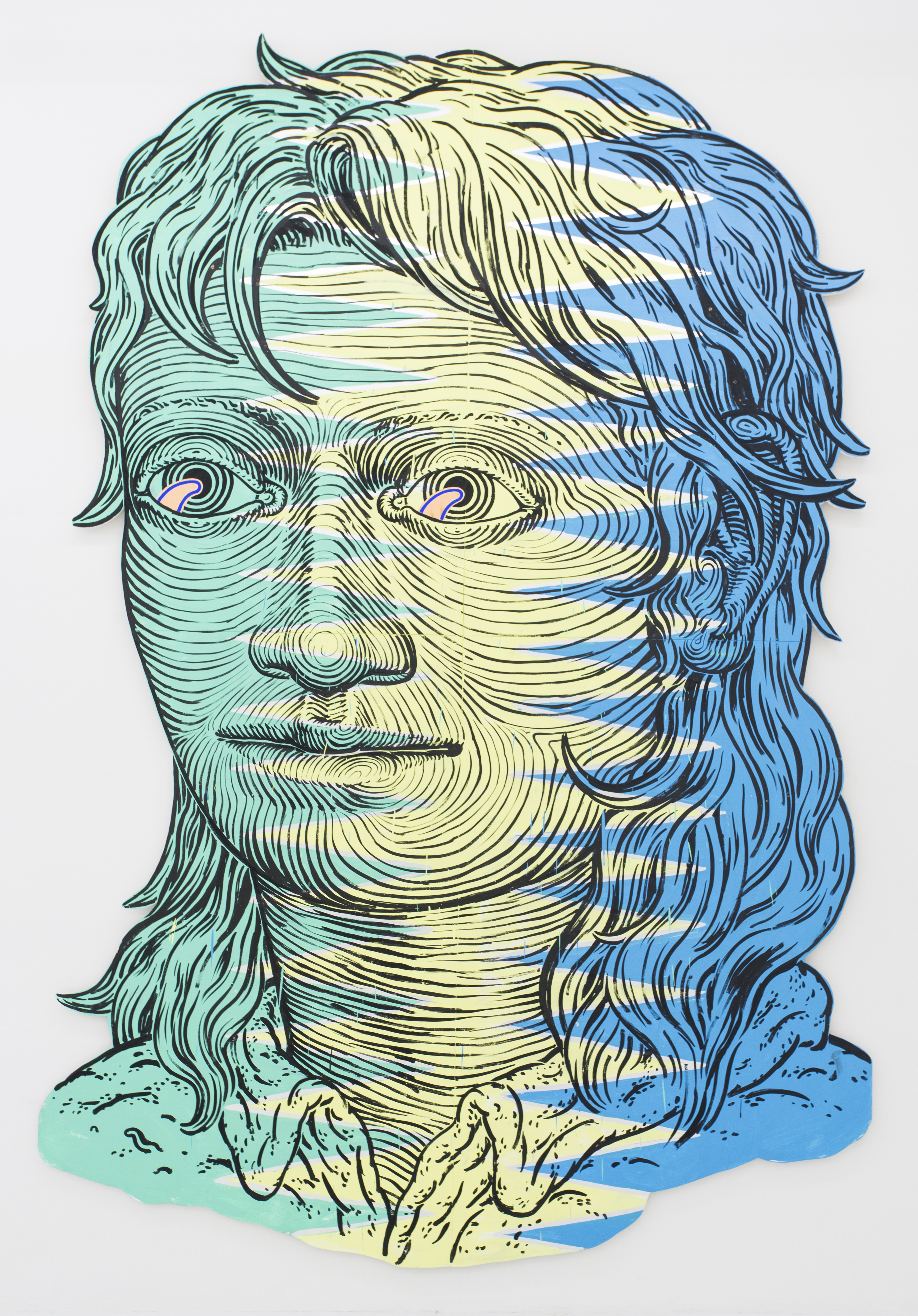

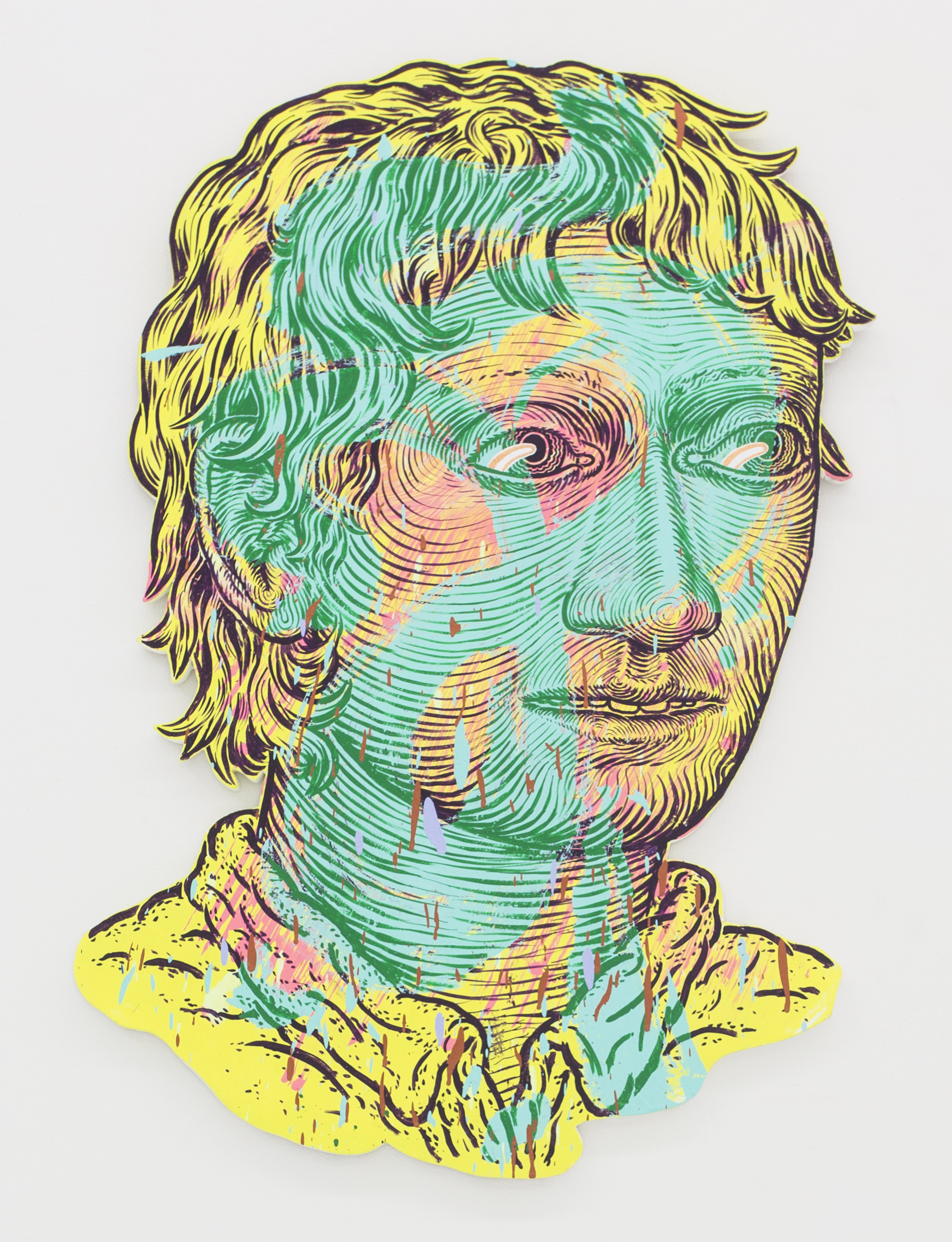

The Hole is proud to announce a new solo exhibition by Taylor McKimens. In this tightly conceived exhibition, over twenty new paintings explore the same subject—two people’s heads—inspired by two Greek sculptures from the Metropolitan Museum. These androgynous and perplexingly blank heads are the common denominator in a diverse show where McKimens experiments boldly with formal painting aspects like color, line, volume and figure-ground relationships. Employing his traditional painting and drawing talents, and pushing past their limitations, the artist fixes his subject matter so he can experiment within these restrictions to innovate. The result is a very atypical figurative painting show that broadens how figuration can be engaged with today.

Taylor McKimens has been known for years as a painter of “American Life”, making large and narrative paintings that feature rural tableaux, economically marginalized people, overlooked and often beautiful details of the natural world and cultural debris. He is such an evocative visual storyteller and technical draftsman that viewers may not have noticed that his paintings were getting more and more experimental in technique. Over the past few years the backgrounds have gotten abstract and hectic, colors have gone haywire as he switches color mid-brushstroke and inverts shadows and highlights, and topographical line work has proliferated to both render volumes and collapse space.

In this new body of work we see paintings that are bouncing around the extremes of where drawing and painting intersect, where figuration and abstraction resonate. There are works where slashes of color inversion crisscross the piece, and the lines go from red to green to brown and back again as you move across the figure’s cheek. Works experiment with black and white tonality, reflective paints, stains and spattered drop cloths. Even just within each painted eyeball in the series of heads, the shape and color of the highlight ranges from pink and green semicircles to white stars to green serrated ovals. McKimens sees himself as “part technical draftsman and part lazy laborer just trying to finish the job,” often composing something highly technical and flashy then wiping it out with superfluous contour lines or illogically contrasting color.

McKimens was drawn to these heads because “they seemed to be having all emotions simultaneously” and were titled in the museum collection “Head of Youth” because of their indeterminate gender and identity. In this show the serenely sphinx-like faces are a template through which the artist can systematically explore the concerns of painting and drawing, not ignoring the sentimental implications of rendering a human likeness, but by their blankness and repetition allowing the viewer to move on to other aspects of the work besides “who is this” or “what can I learn about this person.”

“I’ve read that many successful people wear the same outfit every day. It’s one less decision so more time can be spent on more important trains of thought. These paintings have that same basic idea. I like the idea of a head being used as an abstract compositional element. Every brushstroke evokes a certain feeling: a line, a triangle, a square, or a drip all evoke different things and are individual ingredients that when combined create a recipe with harmonizing and contrasting elements. I think a head can be an element just the same as any formal abstract element, so in that way I welcome narrative with these new paintings. But rather than tell a specific story, I’d like to evoke feeling and stir up preconceived ideas about what a head like this might mean, or what figurative painting looks like.”

If the works were purely abstract they would be about, perhaps, how to “draw with color” and after viewing the series of similar faces they do become almost abstracted; however, the lure of the face with its hypnotic, spiraling irises always persists, challenging our emotional responses:

“I want these to essentially be abstract paintings, but I like serving up a dollop of big-eyed figurative imagery smack in the middle of it to confront the fear of sentimentality and emotion in art. I think soul is an essential ingredient prevalent in all types of art from music, food, writing etc., but has been largely absent in highbrow art. I’d like to poke at that sensitive spot and shine light on how ridiculous the fear of sentiment is in high art. Its absence often seems more like insecurity than an enlightened omission.”

Can paintings be both “about something” and formally sophisticated today? Why does figurative painting seem to have “too much baggage” to a more abstract-inclined audience, or why can it often veer into being “embarrassing”? The artist explores the zone in between:

“People with too strong of a love for figurative art often can tend to be very conservative and overly respectful to the traditions of realistic or academic approaches to image making. They tend to be the Civil War re-enactors of the art world, making artwork that has little to do with genuinely reflecting on the era we currently live in.

I have a strong love of abstract art and formal ideas as well but am wary of a tendency toward too-reductive pursuits that ultimately steer artists away from powerful and volatile subject matter, ending up with a safe sort of boring visual Muzak.”

Growing as an artist through comic or illustrative styles of figuration, McKimens’ background informs his approach to “high art” as an outsider and insider:

“Growing up in a small desert town on the Mexican border, I had no access to museums or galleries to see original art. I learned how to make art by looking at print: the bumblebee on a Cheerios box, cartoons in the paper, Ratfink, comics, crummy illustrations with bad printing on Mexican products, the lines on George Washington’s face on a dollar bill. I think it’s a very common story for American artists raised outside of big cities with their significant museums and deep European traditions. When most of these artists go to art school they’re usually forced into the decision of either wiping out their past identity and conforming to the look of ‘high art’, or the more prideful yet limiting path of rejecting the art world entirely and pursuing a more ‘low brow’ art.

I see my graphic, pop roots as a strength and reflective of a very American story, and I apply them to the various painting traditions that I have come to understand and love. These paintings are about exploring the ways those two worlds clash and vibrate with each other visually, spiritually and conceptually.”

The works in exhibition seek to exist between genres of figurative or abstract, highbrow or lowbrow, sentimental and academic, and all the other limiting binaries of interpretation to be both volatile and conservative, soulful and austere, containing elements that appeal to both sides in these paintings, or as the artist puts it, “ambassadors between the two mindsets.” When the paintings stop being anchored to identity and narrative, how much more content can they take on instead?

McKimens (b. 1976 Winterhaven, CA) has exhibited widely in both gallery and museum shows, and has work in many prominent collections. Notable exhibitions include solo and group exhibition at Deitch Projects, NYC and Loyal Galerie in Sweden, group exhibitions at The Hole NYC, the Macro Museum, Rome and the Garage Center in Moscow. Some recent exhibitions include a solo show at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, Japan; When Things Get Back to Normal, Galerie Zurcher, Paris curated by Peter Saul; Spaghetti and Beach Balls, curated by Donald Baechler, Studio d’Arte Raffaelli, Trento, Italy; and Commissions by Paul Bright, a solo exhibition of recent work February 2015 in NYC.